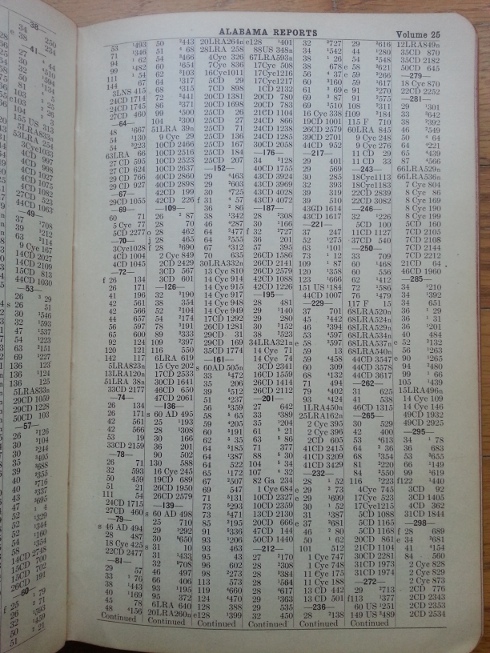

From early 2003 to late 2005 I wrote a blog on oreillynet.com that I called Thinking About Linking. The last entry summarizes what I covered and my experiences with that blog, but today I wanted to republish my favorite entry from that blog on the tenth anniversary of its original publication. It's the same as the 2003 version except that I updated one link. On the right: a page from Shepard's 1902 "Shepard's Alabama Citations," which I bought on ebay. (My comment below about link typing would certainly need updating now, given my experience with RDF.)

Frank Shepard was a salesman for a Chicago legal publisher. Shortly after the American Civil War, he noticed that when one court case overruled, criticized, or otherwise cited another, lawyers often jotted a note about it in the margin of the reporter volume with the cited case's text. For example, upon learning that the judge in the case known as “La Bourgogne” (210 U.S. 95) made a negative references to the “Moore v. American Transportation Company” (65 U.S. 1) case, a lawyer might turn to page 1 in volume 65 of the U.S. Supreme Court case reporter and write “210 U.S. 95, negative” in the margin next to the Moore case. This way, if if the Moore case ever came up in court, the lawyer would have a better idea of its exact value.

Shepard had an idea: if he printed gummed labels for each case listing the cases that cited it, he could save the lawyers the trouble of writing in these references by hand. He built a business out of selling these inter-case links to the legal profession and named the company after himself: Shepard's. (Full disclosure: since Reed Elsevier acquired Shepard's in the mid-1990s, Shepard's Citations has been a product of my employer, LexisNexis. Other than some occasional XSLT advice to the folks in Colorado Springs, where Shepard's has been based since 1947, I don't do any work on that particular product.) In one sense, the stickers they produced in 1873 were already more sophisticated than web links, because if more than one case had cited the same case, the sticker for that case added a one-to-many link to it.

To help the lawyers quickly learn why one case had been cited by another, Shepard's started including one-letter codes to show that the citing case had overruled, criticized, modified, or applied some other treatment to the cited case. Now their links had link types: indications about the nature of the links to give a clue about why they might be worth traversing.

The stickers, or “Adhesive Annotations,” became very popular. While sitting on the Massachusetts Supreme Judicial Court, future United States Supreme Court Justice Oliver Wendell Holmes Jr. wrote “I regard Shepard's Massachusetts Annotations as the most thorough labor-saving device that has even been brought to my attention. No one owning a set of reports can afford to be without one.”

Before the nineteenth century came to a close, the company began producing alternatives to the sticker collections: bound books that listed, for each case, the cases that cited it and codes describing the citing case's treatment. Today, we call this separation of the links from the linked resources “out-of-line links.”

The books became so popular that their inventor's last name became a verb. Any lawyer or law student knows that to Shepardize a case is to find out all relevant cases that cite it. Of course, automating the storage and lookup of these links is much easier with software, and it's all online now. When you view a case using LexisNexis, clicking the “Shepardize” link displays a list of citing cases with links to the full text of those cases. This saves a lot of running around a law library, which was how the links were followed for the first century of their existence. (LexisNexis's chief competitor, WestLaw, has a competing on-line product called KeyCite.)

The success of Frank Shepard's invention tells us several things about linking:

-

Link typing can add real value to a linking application. If a lawyer who's going to bring up a case in court Shepardizes it and sees only codes for positive treatment, there's little need to look up the citing cases. If other cases criticized the case to be cited, however, it's his job to find out why. (Too bad it's so difficult to find other examples of link typing adding obvious value!)

-

Out-of-line links can sometimes be more useful than in-line links. The web and other hypertext systems leading up to it have conditioned many to think of a link as something that connects the resource they're looking at to a single other resource somewhere else, but links can be more than that. Shepard's customers found that having all the citation links in a single set of books instead of as a set of stickers to be spread around hundreds of volumes can make the research go much more quickly, especially with the treatment codes added to the link identifiers to give clues about whether the links are worth traversing.

-

It's not about the technology, but about the information. Just as a well-written song can work well when performed by different bands, a good linking application can still have value when implemented using different technologies.

Please add any comments to this Google+ post.